A Major Postgres Upgrade with Zero Downtime

Stepan Parunashvili, Daniel Woelfel·Jan 29th, 2025

We’re Instant, a modern Firebase. You can spin up a database and make queries within a minute — no login required.

Right before Christmas we discovered that our Aurora Postgres instance needed a major version upgrade. We found a great essay by the Lyft team, showing how they ran their upgrade with about 7 minutes of downtime.

We started with Lyft’s checklist but made some changes, particularly with how we switched masters. In our process we got to 0 seconds of downtime.

Doing a major version upgrade is stressful, and reading other’s reports definitely helped us along the way. So we wanted to write an experience report of our own, in the hopes that it’s as useful to you as reading others were for us.

In this write-up we’ll share the path we took — from false starts, to gotchas, to the steps that ultimately worked. Fair warning, our system runs at a modest scale. We have less than a terabyte of data, we read about 1.8 million tuples per second, and write about 500 tuples per second as of this writing. If you run at a much higher scale, this may be less relevant to you.

With all that said, let’s get into the story!

State of Affairs

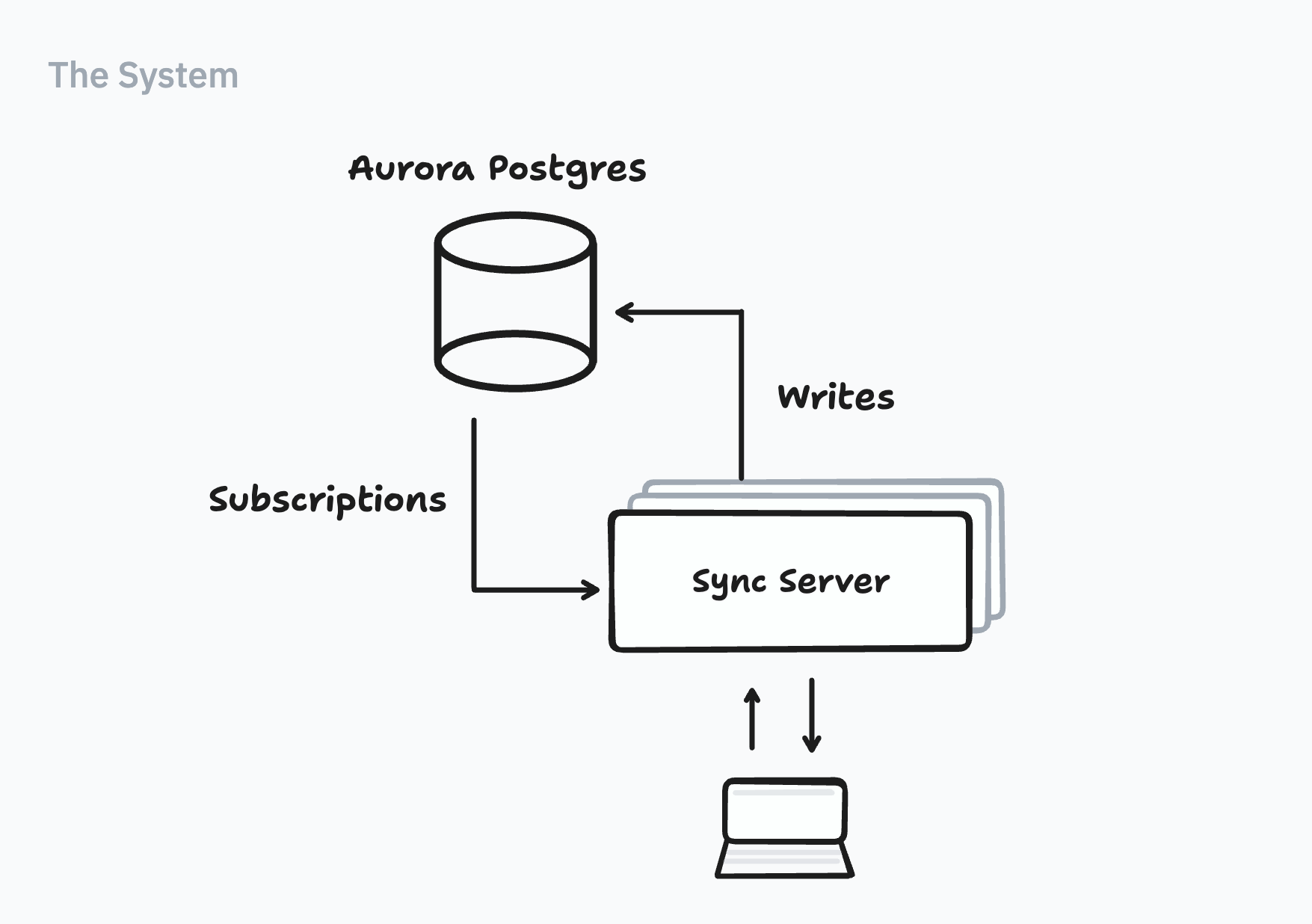

Let’s start with a brief outline of our system:

Browsers connect to sync servers. Sync servers keep track of active queries. Sync servers also listen to Postgres’ write-ahead log; they take transactions, find affected queries, and send novelty back to browsers. [1] Crucially, all Instant databases are hosted under one Aurora Postgres instance. [2]

Trouble Erupts

After our open source launch in August [3], we experienced about a 100x increase in throughput. For the first 2 months, whenever we saw perf issues they usually lived in our Client SDK or the Sync Server. When we hit a new high in December though, our Aurora Postgres instance started to spike in CPU and stumble.

To give us breathing room, we kept upgrading the size of the machine, until we reached db.r6g.16xlarge. [4] We had to do something about the queries we were writing.

Sometimes, new is better than old

We started to reproduce slow queries locally and began to optimize them. Within the first hour we noticed something strange: one teammate constantly reported faster query results then the rest of us.

Turns out this teammate was running Postgres 16, while most of us (and our production instance) were running Postgres 13.

We did some more backtesting and realized that Postgres 16 improved many of the egregious queries by 30% or more. Not bad. There came our first learning: sometimes, just upgrading Postgres is a great way to improve perf. [5]

So we thought, let’s upgrade to Postgres 16. Now how do we go about it?

False Starts

We were a team of 4 and we were in a crunch. If we could find a quick option we’d have been happy to take it. Here’s what we tried:

1) In-Place Upgrades...but they take 15 minutes

The easiest choice would have been to run an in-place upgrade. Put the database in maintenance mode, upgrade major versions, then turn it back on again. In RDS console you can do this with a few button clicks.

The big problem is the downtime. Your DB is in maintenance mode for the entirety of the upgrade. The Lyft team said an in-place upgrade would have caused them a 30 minute outage.

We wanted to test this for ourselves though, in case a smaller database upgraded more quickly. So we cloned our production database and tested an in-place upgrade. Even with our smaller size, it took about 15 minutes for the clone to come back online.

Crunch or not, a 15-minute outage was off the table for us. Since launch we had folks sign up across the U.S, Europe and Asia; traffic ebbed and flowed, but there wasn’t a period where 15 minutes of downtime felt tolerable.

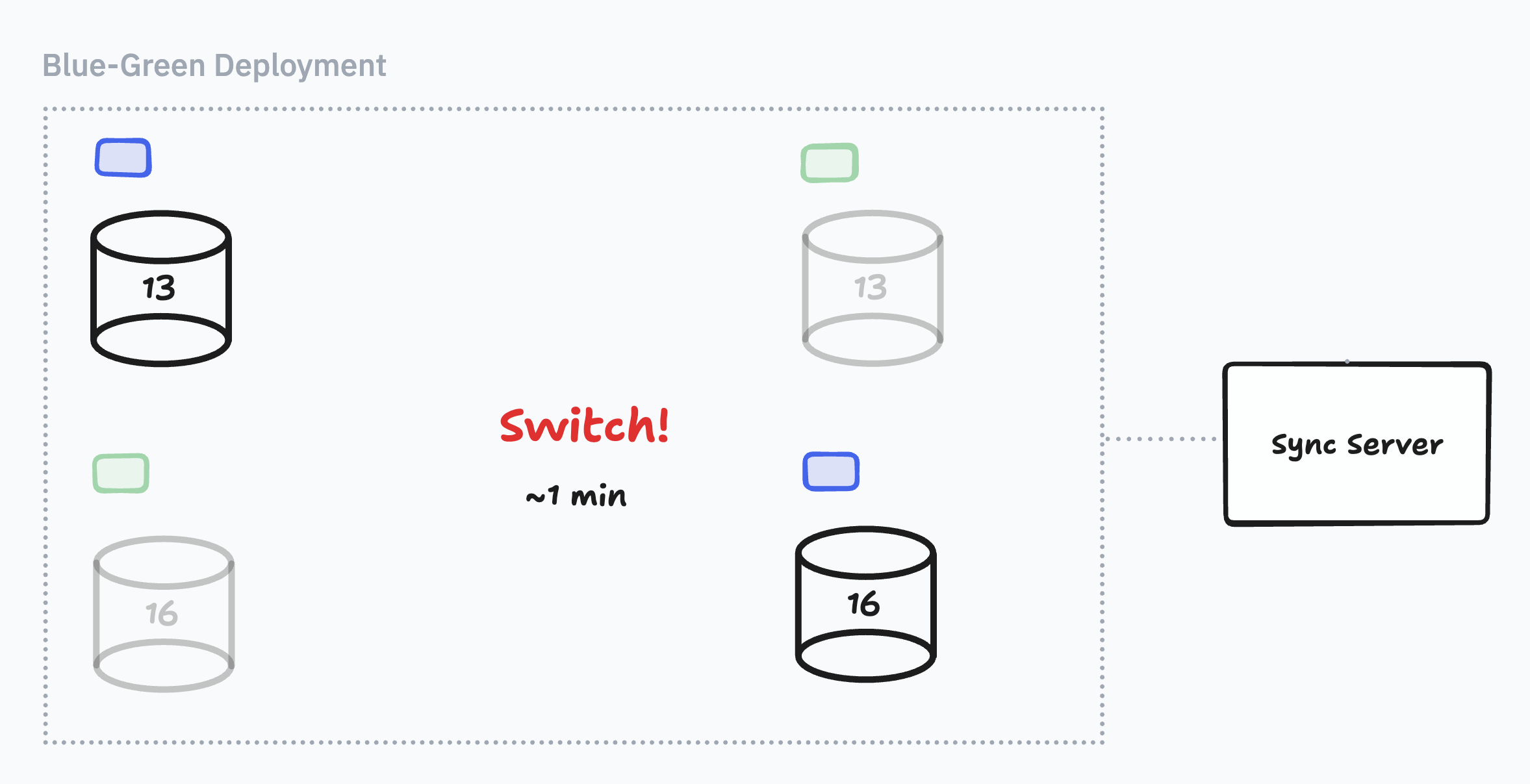

2) Blue-Green Deployments...but you can’t have active replication slots

Well, Aurora Postgres also has blue-green deployments. AWS spins up an upgraded replica for you, and you can switch masters with a button click. They promise about a minute of downtime.

With such little operational effort, a minute of downtime sounded like a great option for us.

So we cloned our DB and tested a blue-green deployment. Yup, the connection came back in a minute! It looked like we were done. Until we tried a full rehearsal.

We spun up a complete staging environment, this time with active sync servers and connected clients. Now the blue-green deployment would go on for 30 minutes, and then break with a configuration error:

Creation of blue/green deployment failed due to incompatible parameter settings. See link to help resolve the issues, then delete and recreate the blue/green deployment.

The next few hours were frustrating: we would change a setting, start again, wait 30 minutes, and invariably end up with the same error.

Once we exhausted the suggestions from this error message, we began a process of elimination: when did the upgrade work, and what change made it fail? Eliminating the sync servers revealed the issue: active replication slots.

Remember how our sync servers listen to Postgres’ write-ahead log? To do this, we opened replication slots. We couldn’t create a blue-green deployment when the master DB had active replication slots. The AWS docs did not mention this. [6]

At least this experience highlighted a learning: always run a rehearsal that’s as close to production as possible, you never know what you’ll find.

In order to stop using replication slots we’d have to disconnect our sync servers. But then we would lose reactivity, potentially for 30 minutes. Apps would appear broken if we queries were out of sync that long; blue-green deployments were off the table too.

A Plan for Going Manual

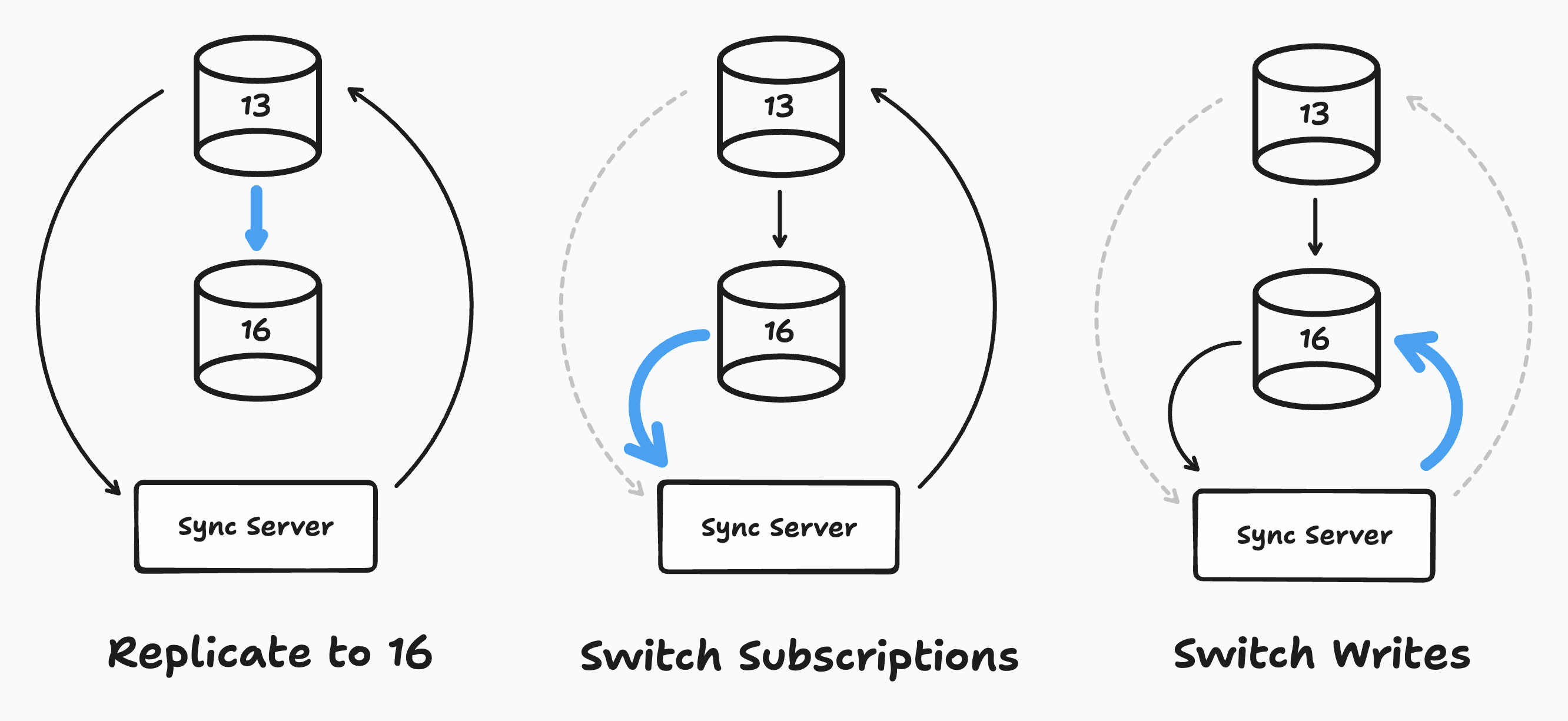

When the managed options don’t work, it’s time to go manual. We knew that a manual upgrade would have to involve three steps:

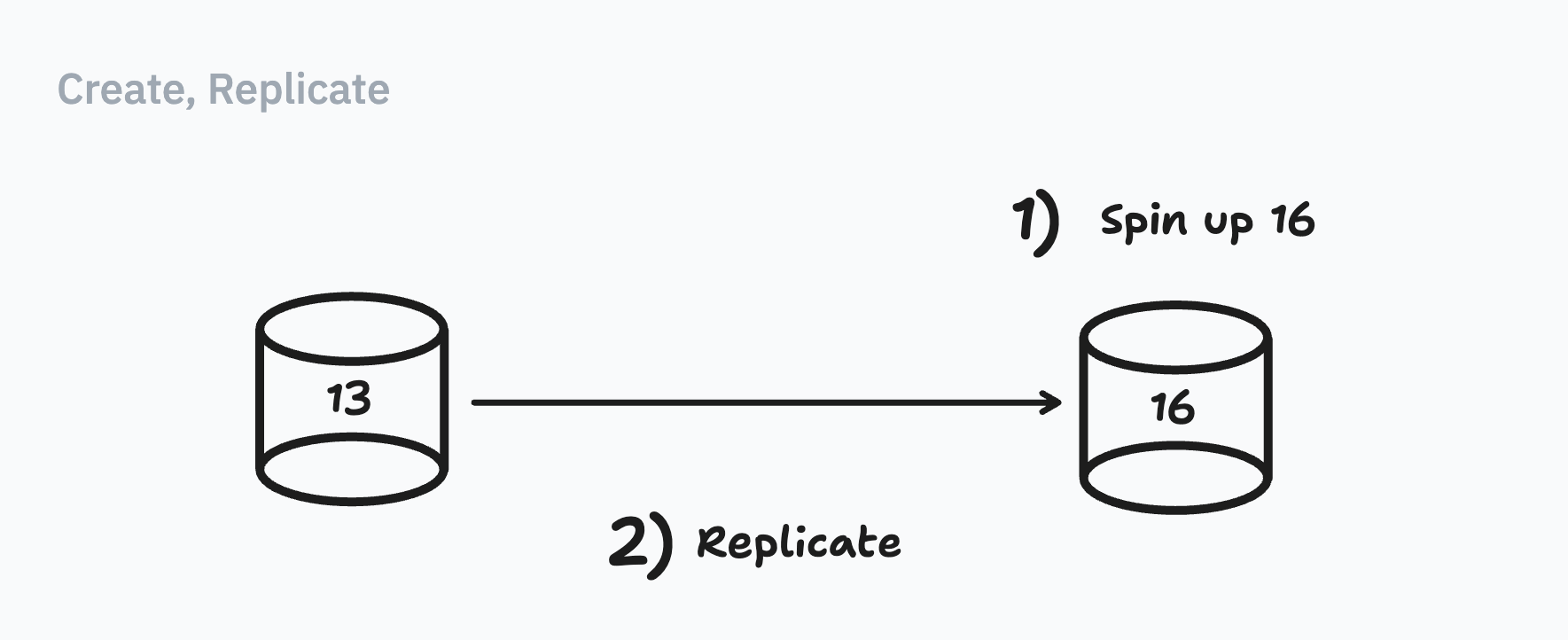

First, we would stand up a new replica running Postgres 16 — Let’s call this machine "16". Once 16 was running, we could get our sync servers to subscribe to 16. The remaining step would be to switch writes "all in one go" (what this meant TBD) to 16. When that was done, migration done.

Now to figure out the steps

1) Replicate to 16

The first problem was to create our replica running Postgres 16.

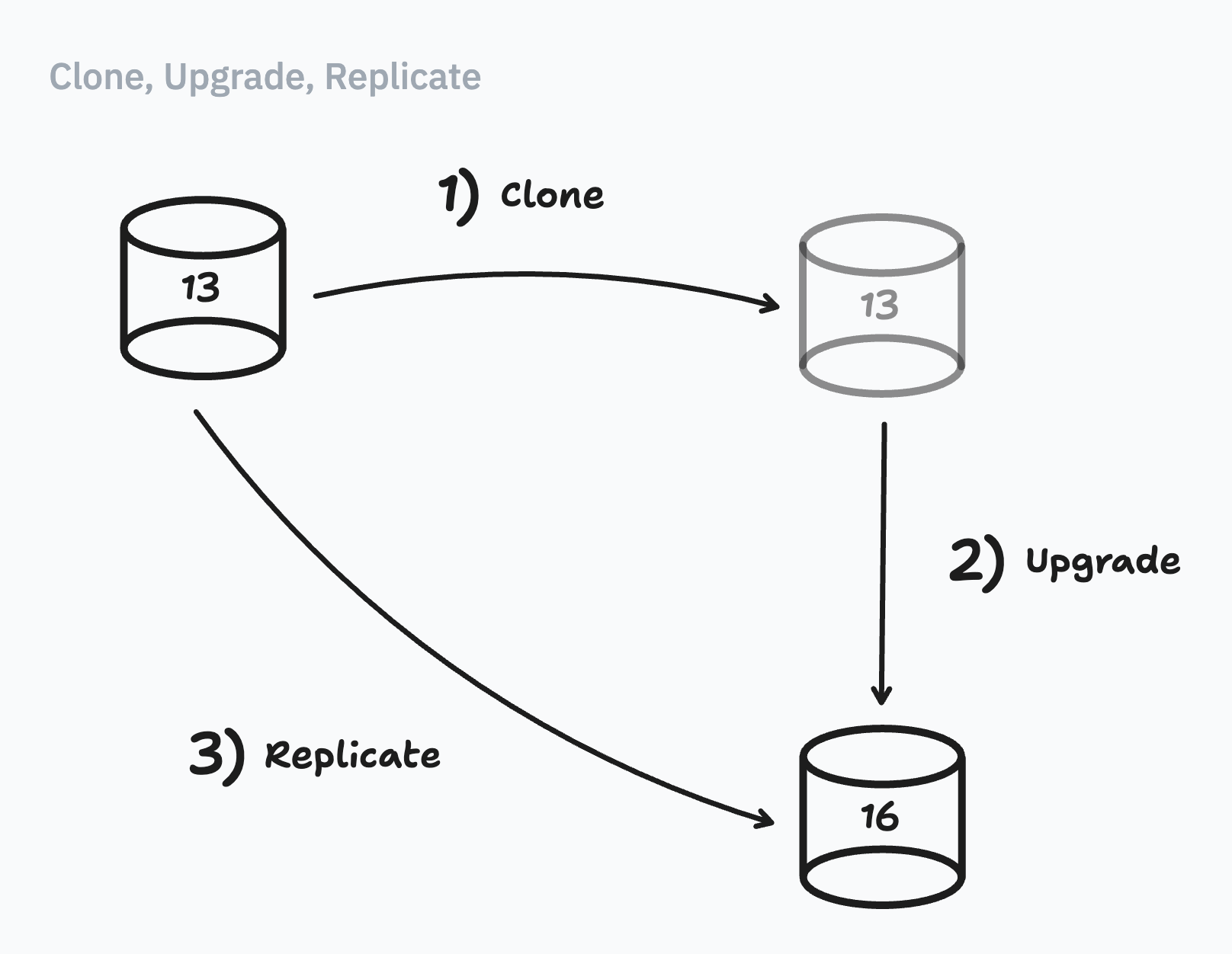

a) Clone-Upgrade-Replicate led to...lost data

Lyft had a great series of steps to create a replica, so we tried to follow it. There were three stages:

First, we clone our database, then we upgrade our clone, and then we start replication. By the end, our clone would have become a replica running Postgres 16.

Steps 1 (clone) & 2 (upgrade) worked great. The trouble started with step 3 (replicate).

Lost PG functions

When we turned on replication, we saw this error:

:ERROR: function is_jsonb_valid_timestamp(jsonb) does not exist at character 1

That’s weird. We did have a custom Postgres function called

is_jsonb_valid_timestamp. And the function existed on both machines; if we logged in with PSQL, we could write queries:select is_jsonb_valid_timestamp('1724344362000'::jsonb);

is_jsonb_valid_timestamp

--------------------------

t

We thought maybe there was an error with our WAL level, or maybe some input worked in 13, but stopped working in 16.

Search paths

So we went down a rabbit hole investigating and searching in PG’s mailing list. Finally, we discovered the problem was search paths. [7]

show search_path;

search_path

-----------------

"$user", public

Postgres stores custom functions in a schema. When you write a function in your query, PG uses a

search_path to decide which schema to look into. During replication, Postgres was having trouble finding our function. To get around this issue, we wrote a PR to add the public prefix explicitly in all our function definitions:-- Before:

create or replace function is_jsonb_valid_timestamp(value jsonb)

-- After: 👇

create or replace function public.is_jsonb_valid_timestamp(value jsonb)

Note to us: make sure to use

public in all our function definitions. [8]With PG functions working, 3) replicate ran smoothly! Or so we thought.

Missing data

For all intents and purposes, our new clone looked like a functioning replica. But we wanted to absolutely make sure that we didn’t lose any data.

Thankfully, we had a special

transactions table — it’s an immutable table we use internally [9]:instant=> \d transactions;

Column | Type | -- ...

------------+-----------------------------+

id | bigint |

app_id | uuid |

created_at | timestamp without time zone |

Since we never modify rows, we could also use the

transactions table for quick sanity checks — was there any data lost in the table? Here’s the query we ran to do that:-- On 13

select max(id) from transactions;

select count(*) from transactions where id < :max-id;

-- Wait for :max-id to replicate ...

-- On 16

select COUNT(*) from transactions where id < :max-id;

To our surprise...we found 13 missing transactions! That definitely stumped us. We weren’t quite sure where the data loss came from [10]

b) Create, Replicate...worked great!

So we went back to the drawing board. One problem with our replica checklist was that it had about 13 steps in it. If we could remove the number of steps, perhaps we could kill whatever caused this data loss.

So we cooked up an alternate approach:

Instead of creating, cloning, and then upgrading, we would start with a fresh database running Postgres 16, and replicate from scratch. Lyft chose to clone their DB, because they had over 30TB of data and could leverage Aurora Cloning. But we had less than a terabyte of data; starting replication from scratch wasn’t a big deal for us. [11]

So we created a checklist and ended up with 7 steps:

Checklist: Create an upgraded Replica

-

16: Create a new Postgres Aurora Database on Postgres 16.Make sure to set

wal_level = logical -

13: Extract the schema

pg_dump ${DATABASE_URL} --schema-only -f dump.schema.sql -

16: Import the schema into 16

psql ${NEW_DATABASE_URL} -f dump.schema.sql -

13: Create a publication

create publication pub_all_table for all tables; -

16: Create a subscription with copy_data = true

create subscription pub_from_scratch connection 'host=host_here dbname=name_here port=5432 user=user_here password=password_here' publication pub_from_scratch with ( copy_data = true, create_slot = true, enabled = true, connect = true, slot_name = 'pub_from_scratch' ); -

Confirm that there’s no data loss

-- On 13 select max(id) from transactions; select count(*) from transactions where id < :max-id; -- Wait for :max-id to replicate ... -- On 16 select count(*) from transactions where id < :max-id; -

16: Run vacuum analyze

vacuum (verbose, analyze, full);

We ran step 6 with bated breath...and it all turned out well! [12] Now we had a replica running Postgres 16.

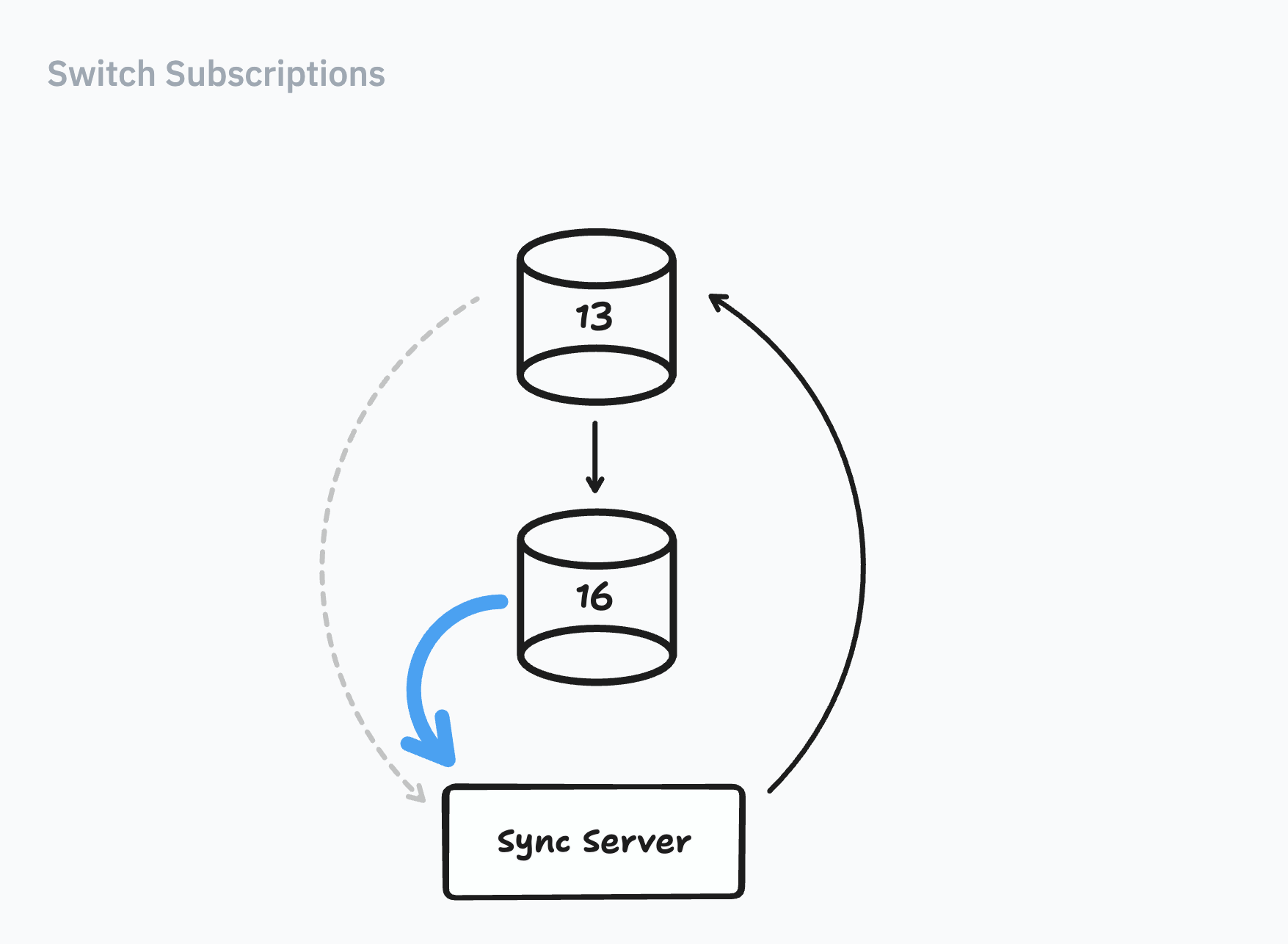

2) Switching Subscriptions

Next step, to switch subscriptions. Let’s remind ourselves what we’re looking to do:

We’d need to get our sync servers to create replication slots in 16, rather than 13.

To do this, we added a

next-database-url variable to our sync servers. During startup, if next-database-url was set, sync servers would subscribe from there:;; invalidator.clj

;; `start` runs when the machine boots up

(defn start

([process-id]

; ...

(wal/start-worker {:conn-config

(or (config/get-next-aurora-config)

;; Use the next db so that we don't

;; have to worry about restarting the

;; invalidator when failing over to a

;; new db.

(config/get-aurora-config))})

; ...

))

Once we deployed this change, sync servers replicated from 16. Phew, this was at least one step in the story that didn’t feel nerve-wracking!

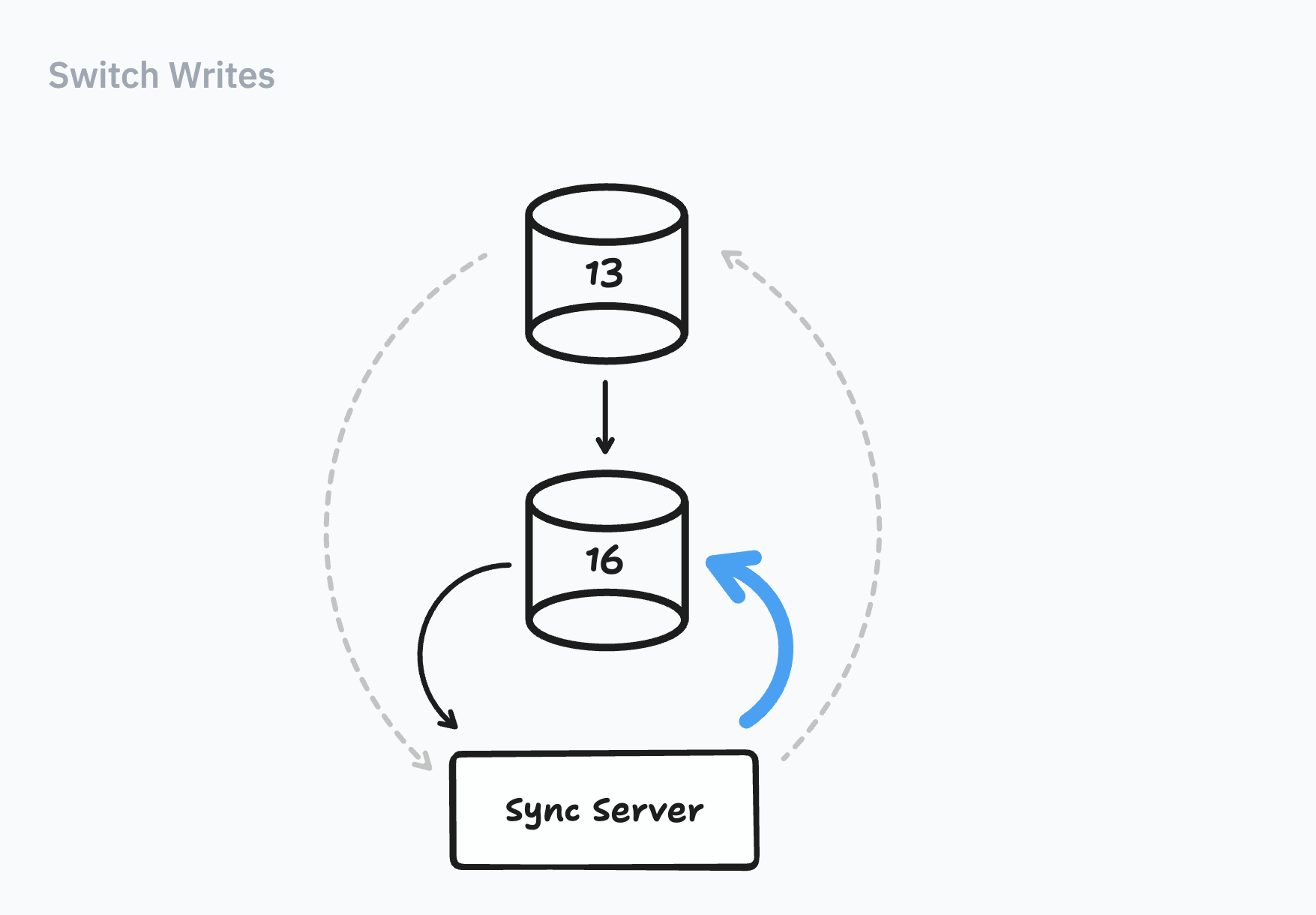

3) Switching Writes

Now to worry about writes:

Ultimately, we needed to click some button and trigger a switch. To make the switch work, we’d need to follow two rules:

-

16 must be caught upIf there are any writes in 13 that haven’t replicated to 16 yet, we can’t turn on writes to 16. Otherwise transactions would come in the wrong order

-

Once caught up, all new writes must go to 16If any write accidentally goes to 13, we could lose data.

So, how could we follow these rules?

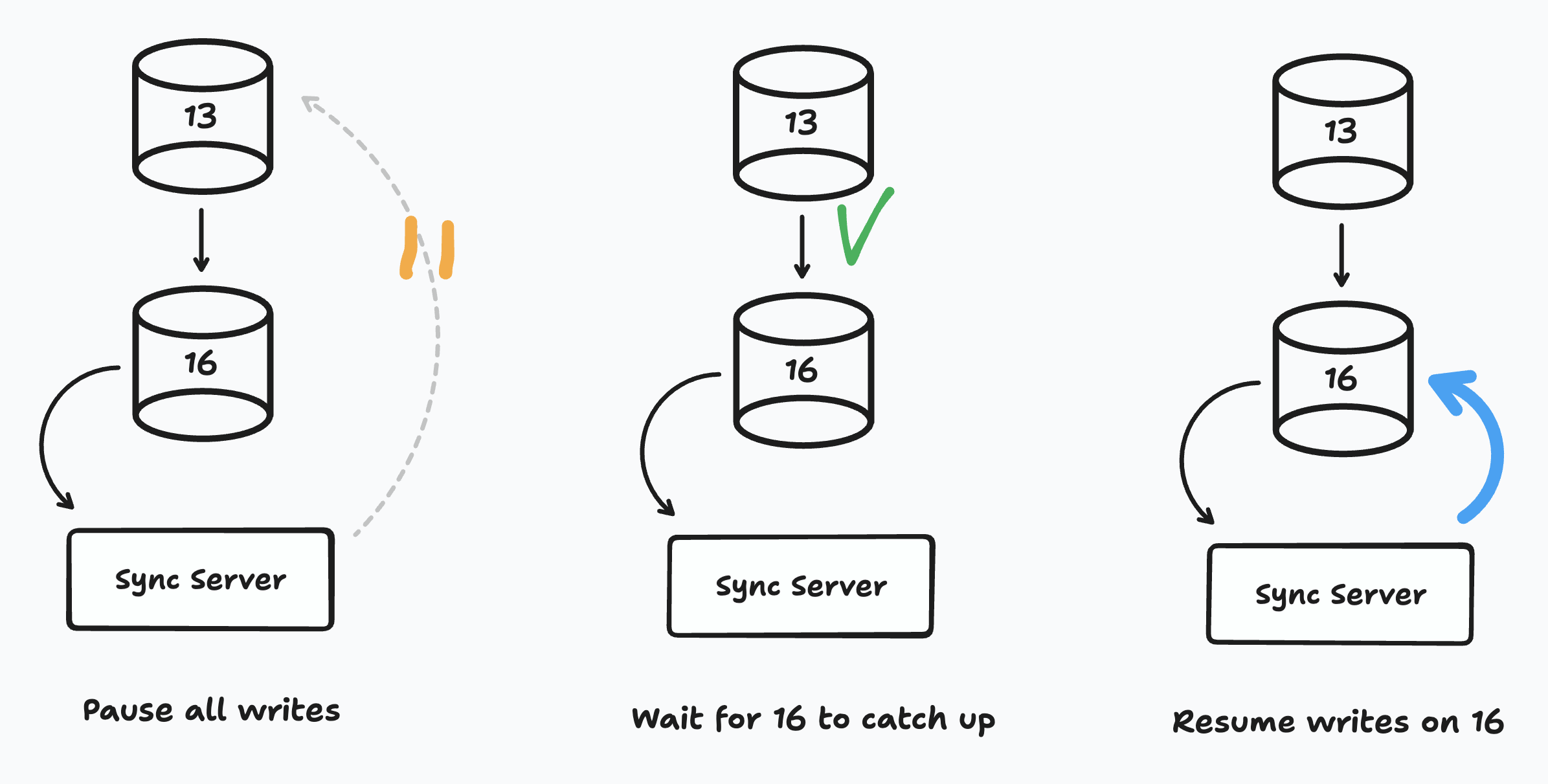

We could stop the world...but that’s downtime

The simplest way to switch writes would have been to stop the world:

- Turn off all writes.

- Wait for 16 to catch up

- Enable writes again — this time they all go to 16

If we manually executed each step in ‘stop the world', we’d have about a minute of downtime. We could write a function which did these steps for us, and get to only a few seconds of downtime. But we had already spent a day setting up our manual method, could we do better?

Since we were switching manually we had finer control over our connections. We realized that with just a little bit more work...we could have no downtime at all!

Or we could write an algorithm with zero downtime!

Our co-author Daniel shared an algorithm he used at his previous startup:

First, we pause all new transactions. Then, we wait for active transactions to complete and for 16 to catch up. Finally we unpause all transactions and have them go to 16. If we did this right, we could switch major versions without any downtime at all!

The benefits of being small

Sounds good in theory, but it can be hard to pull off. Unless of course you run at a modest scale.

Our switching algorithm hinges on being able to control all active connections. If you have tons of machines, how could you control all active connections?

Well, since our throughput was still modest, we could temporarily scale our sync servers down to just one giant machine. Clojure and Java came handy here too. We had threads and the JVM is efficient, so we could take full advantage of the m6a.16xlarge sync server we moved to for the switch.

Writing out a failover function

So we went forward and translated our zero-downtime algorithm into code. Here’s how it looked:

(defn do-failover-to-new-db []

(let [prev-pool aurora/-conn-pool

next-pool (start-new-pool next-config)

next-pool-promise (promise)]

;; 1. Make new connections wait

(alter-var-root #'aurora/conn-pool (fn [_] (fn [] @next-pool-promise)))

;; 2. Give existing transactions 2.5 seconds to complete.

(Thread/sleep 2500)

;; Cancel the rest

(sql/cancel-in-progress sql/default-statement-tracker)

;; 3. Wait for 16 to catch up

(let [tx (transaction-model/create! aurora/-conn-pool

{:app-id (config/instant-config-app-id)})]

(loop [i 0]

(if-let [row (sql/select-one next-pool

["select * from transactions where app_id = ?::uuid and id = ?::bigint"

(config/instant-config-app-id) (:id tx)])]

(println "we are caught up!")

;; Still waiting...

(do (Thread/sleep 50)

(recur inc i)))))

;; 4 accept new connections!

(deliver next-pool-promise next-pool)

(alter-var-root #'aurora/-conn-pool (fn [_] next-pool))))

We spun up staging again, ran our failover function...buut transactions failed again. We were getting unique constraint violations on our transactions table.

Don’t forget sequences

This time the fix was easy to catch: sequences. Postgres does not replicate sequence data. This meant that when a new

transaction row was created, we were using ids that already existed.To fix it, we incremented our sequences in the failover function:

- (println "we are caught up!")

+ (sql/execute! next-pool

+ ["select setval('transactions_id_seq', ?::bigint, true)"

+ (+ (:id row) 1000)])

This time we ran the failover function...and it worked great!

If you’re curious, here’s how the actual failover function looked for production.

Running in Prod

Now that we had a good practice run, we got ourselves ready, had our sparkling waters in hand, and began to run our steps in production.

After about a 3.5 second pause [13], the failover function completed smoothly! We had a new Postgres instance serving requests, and best of all, nobody noticed. [14]

Future Improvements

Our

do-failover-to-new-db worked at our scale, but will probably fail us in a few months. There are two improvements we plan to make:- We paused both writes and reads. But technically we don’t need to pause reads. Daniel pushed up a PR to be explicit about read-only connections. In the future we can skip pausing them.

- In December we were able to scale down to one big machine. We’re approaching the limits to one big machine today. [15] We’re going to try to evolve this into a kind of

two-phase-commit, where each machine reports their stage, and a coordinator progresses when all machines hit the same stage.

Fin

Aand that’s our story of how did our major version upgrade. We wanted to finish up with a summary of learnings, in the hopes that’s easier for you to get back to this essay when you’re considering an upgrade. Here’s what we wish we knew when we started:

- Sometimes, newer Postgres versions improve perf. Make sure to check this if you face perf issues.

- If you need to upgrade

- Pick a buddy if you can, it’s a lot more fun (and less nerve-racking) to do this with a partner.

- Before you do anything in production, do a full rehearsal. Use a staging environment that mimics production as closely as possible

- If you are okay with 15 minutes of downtime, do an in-place upgrade

- If you don’t have active replication slots and are okay with a minute of downtime, try a blue-green deployment

- When you need to do a manual upgrade:

- If you can, skip cloning and create a replica from scratch. There are only 7 steps

- If you wrote custom pg functions, make sure to check your search_path

- Do some sanity checks to make sure you don’t lose data

- If you can get writes down to one machine, try our algorithm for zero downtime

Hopefully, this was a fun read for you :)

Thanks to Nikita Prokopov, Joe Averbukh, Martin Raison, Irakli Safareli, Ian Sinnott for reviewing drafts of this essay

Footnotes

-

Our sync strategy was inspired by Figma’s LiveGraph and Asana’s Luna. The LiveGraph team wrote a great essay that explains the sync strategy. You can read our original design essay to learn more about Instant ↩

-

You may be wondering: how do we host multiple "Instant databases", under one "Aurora database"? The short answer is that we wrote a query engine on top of Postgres. This lets us create a multi-tenant system where we can "spin up" dbs on demand. I hope to share more about this in a separate essay. ↩

-

db.r6g.16xlarge would cost us north of 6K per month. That was out of the question for the kind of traffic we were handling. ↩

-

In case you were wondering, we also looked to optimize the queries. After we upgraded (took about a day and a half), we added a partial index that improved perf another 50% or so. ↩

-

We did see a note about replication in "Switchover Guardrails", but this note is about the second step: after 1) creating a green deployment, we 2) run the switch. ↩

-

The key to discovering this issue was our co-author Daniel’s sleuthing. He planned test upgrades locally: going from 13 → 14 → 15 → 16, to see where things broke. When Daniel tried 13 → 14, it failed. To sanity check things, he then tried a migration from 13 → 13…and that failed too! From there we knew something had to be up with our process. ↩

-

An alternative would have been to enhance the dump file with the search path. We like the idea of being more explicit in our definitions though; especially if we can find a good linter. ↩

-

Why do we have it? We use the transaction’s id column for record-keeping inside sync servers. ↩

-

Though even with 30TB, it would only take a week to transfer at a modest 50 mb/second. ↩

-

You may be wondering — sure, the transactions table was okay, but what if there was data loss in other tables? We wrote a more involved script to check for every table too. We really wanted to make sure there was no data loss. ↩

-

About 2.5 seconds to let active queries complete, and about 1 second for the replica to catch up ↩

-

You may be wondering, how did we run the function? Where’s the feature flag? That’s one more Clojure win: we could SSH into production, and execute this function in our REPL! ↩

-

The big bottleneck is all the active websocket connections on one machine — it slows down the sync engine too much. If we improve perf, perhaps we can get to one big machine again! ↩